An open response to the patent box regime consultation

Incentivizing retention of Canadian IP through preferential tax treatment of income arising from intangible assets

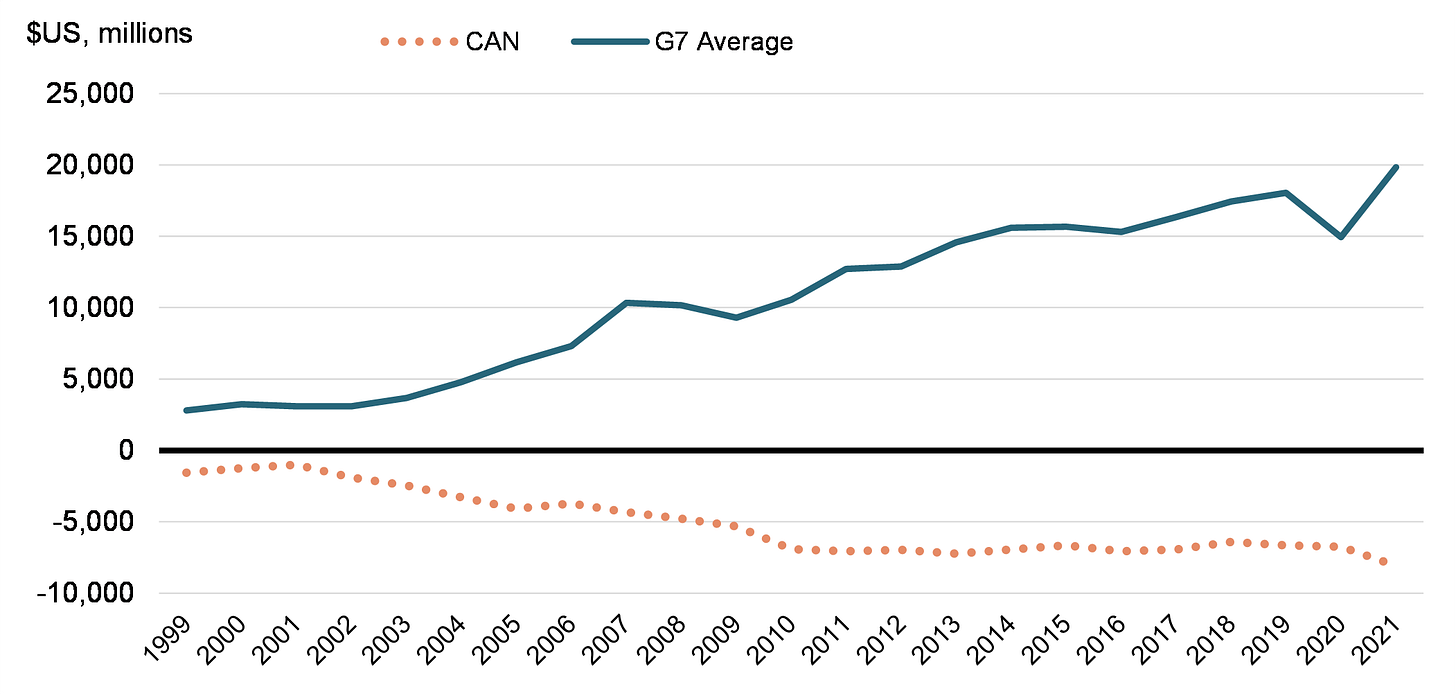

Last week, the government of Canada launched a consultation process to request feedback on reform to the SR&ED program as well as the establishment of a patent box regime to address issues of IP retention in Canada. The chart above, provided alongside the consultation call, shows the extent of the problem: income minus expenditures on the use of IP assets by the Canadian private sector shows a deep and growing deficit, compared to a large and growing surplus on average among the rest of the G7. Given Canada’s highly productive R&D pipeline, the chart is essentially telling us that Canada is paying other countries for access to our own IP, often subsidized by Canadian taxpayers, and that the situation is getting steadily worse.

A patent box regime allows preferential tax treatment for income generated by IP (defined here primarily as patents and copyrighted software) in proportion to the investment made in developing it. The idea is that this will incentivize domestic development, commercialization, and retention of IP assets. Several European countries, as well as the UK, already use a version of this model.

Below, I’ve written an open letter to respond to the questions asked by the consultation call. There is by necessity some repetition between this and my response to the SR&ED consultation.

If you agree with my recommendations, feel free to reuse any of this content to send your own response to the dedicated inbox. Even if you do not, please share awareness of the consultation call, as it is unlikely there will be another chance to address these issues in a meaningful timeframe.

An open response to “Cost-neutral ways to modernize and improve the SR&ED program”

To generate the email with a filled in header in your default mail client, click here

To whom it may concern,

I am a Canadian physicist and entrepreneur operating at the intersection of academic research and early-stage commercialization of innovative technologies. In the course of my career I’ve been involved in the innovation process as an inventor and researchers in an academic lab, responsible for generation of 27 patents filed globally; as founder of a nanotechnology company commercializing part of this portfolio; as a mentor and advisor to other scientists and engineers in the early stages of commercializing their inventions; and more recently as a policy critic attempting to use my experience to turn my experience interacting with the entire spectrum of the early-stage Canadian innovation support system into a productive input to innovation policy development.

While a patent box regime is a positive step, it is not a complete solution to the issues at play. Because exploitation of IP first requires that IP be developed to the point that it can generate income, a patent box will only be effective if implemented together with other innovation policy framework reforms that support development of that IP in the pre-revenue stage, which is where the largest gap in the Canadian innovation support system lies. Below, I summarize four key recommendations for making a patent box regime an effective tool to stimulate domestic development, commercialization, and retention of IP.

Specific Recommendations

While I do recommend implementation of a patent box regime, it should only occur as part of a comprehensive strategy that includes support for development of IP in the pre-revenue phase. IP can only benefit from tax incentives to the extent that it has already been developed to the point that it generates revenue, which can take years. Without concurrent follow-through on reform to SR&ED and NRC IRAP, a patent box is unlikely to address the issues.

The definition of eligible IP is too narrow, given that the report on which the patent box regime is based predates the explosion of AI development that has characterized the last few years. Curated datasets for model training are rapidly becoming at least as important as patents in many competitive firms’ IP strategies. Given the cost and complexity involved in establishing and maintaining high-quality data, the definitions should be expanded to include datasets that can be used for AI and ML training tasks.

Ensuring that the patent box regime is to the long-term economic benefit of Canada requires that firms only be eligible to claim the benefit if their controlling parent company is also a Canadian Controlled Private Corporation (CCPC). If Canadian subsidiaries of foreign multinationals are able to benefit from this patent box regime, the program will only succeed in establishing Canada as a tax haven for exploitation of IP from which income generated ultimately leaves the country.

Evidence-based policy design requires data on long-term use of the IP that benefits from preferential tax treatment. Firms that avail themselves of the associated tax benefits should be required to submit annual reports on the use of relevant IP assets for a period of no less than 10 years following receipt of any benefit under the program, and this requirement should be contractually inherited by any acquirer, assignee, or licensee of that IP. Appropriate metrics should be the subject of a separate consultation call involving all relevant stakeholders.

A detailed rationale for each recommendation follows below the signature. Should you wish to contact me to follow up on any of the points made here, please do not hesitate to reach out in response to this message.

Sincerely,

Kyle Briggs

Detailed Rationale

In contrast to its international peers, Canada has a net balance of payments deficit (receipts minus payments) on charges for the use of IP that has grown over the last two decades (see the chart below). In other words, businesses in Canada outlay more to entities in other countries for the use of IP than they receive from international sources for the same purpose. What sort of dynamics might be underlying this trend? What factors have contributed to Canada's negative balance?

The problem is not limited to the private sector, and starts long before intellectual property has been developed sufficiently to generate revenue.

According to a presentation by Jim Balsillie, Canada’s most successful innovation-supporting university, Waterloo, receives IP licensing revenues of only $269 per million dollars spent on research, compared to Stanford’s $136,000 per million.

Canada’s innovation strategy involves partnering academia with industry at the academic R&D stage, allowing in particular subsidiaries of multinationals to qualify for federal grants if they fund Canadian labs. This practice, while highly successful at producing papers and patents, results in IP that is generally licensed to the multinational or outright assigned.

When combined with a complete lack of support among all public innovation supports for pre-revenue firms and early stage firms, the result is that most IP simply leaves Canada as soon as it is developed, to be commercialized abroad. All technology must cross the valley of death if it is to make it past the patent stage, but in Canada there is no bridge. Very little Canadian intellectual property is commercialized domestically to the point that it generates revenue and could benefit from a patent box regime at all.

The recent case of the battery plant in which Ontario invested is probably the more extreme example of this: a small lab in Halifax is funded by Tesla for a few hundred thousand dollars per year in exchange for the resulting IP, licensed out of Canada for an insignificant fraction of its actual value. Ontario has now committed billions of dollars to subsidize building a battery plant that will produce batteries based on IP from that lab. Canadian taxpayers are subsidizing a foreign firm in exchange for access to Canadian IP.

Would implementation of a patent box regime improve Canada's competitiveness as a location for developing, commercializing, and retaining ownership of IP? With respect to competitiveness as a location for developing IP, how would support through a patent box regime compare to support provided through the SR&ED program?

A patent box regime is not going to improve Canada’s competitiveness as a location for developing IP, but it could contribute to Canada’s competitiveness in commercializing and retaining ownership of that IP if the development issue can be addressed by other policy levers.

As discussed in detail in the previous section, there is very little incentive currently for innovative Canadian startups to commercialize IP in Canada, and tax breaks on R&D spending can only be effective insofar as those companies have developed revenue-generating IP domestically in the first place. Large companies have, on average, a poor track record of commercialization of novel technologies, often instead simply using them as part of their moat.

Combined with a SR&ED overhaul that facilitates early-stage cashflow as per my recommendations on SR&ED reform, and with a long-overdue overhaul of NRC IRAP, a patent box regime could become a long-term incentive to commercialize IP domestically. However, it must be combined with support for the early stages of IP development or there will be little IP retained in Canada to benefit.

How important are tax considerations in decisions regarding where to commercialize IP and where to locate IP? Which factors besides tax rates impact businesses' decisions around where to locate and commercialize IP derived from R&D conducted in Canada? How should the Department of Finance account for these factors in determining how businesses might alter their behaviour in response to implementation of a patent box regime?

Speaking as someone with experience primarily in the very early stages of building deep tech in Canada, tax considerations are of secondary concern to the availability and willingness of the innovation ecosystem at large to provide support in the early stages of IP development. In order to develop IP that could have preferential tax treatment it is first necessary to have the resources to conduct the relevant R&D. For a patent box regime to bring value to Canadian innovators, the rest of the innovation support ecosystem (SR&ED and NRC IRAP in particular, as previously noted) must be reformed to address the complete lack of support for pre-revenue technologies in Canada and to incentivize healthy risk-taking by Canadian private capital.

Speaking as someone who intends to continue contributing to innovation as a founder in the future, the decision on where to base my next company will be largely determined by the availability of investment, both dilutive and non-dilutive, for the earliest stages of building. Before it is possible to benefit from tax breaks on revenues generated from IP, it is first necessary to fund development of that IP to the point that it is revenue-generating. Currently, Canadian innovation policy comprehensively fails to address the pre-revenue stage of development.

What would be a competitive combined federal-provincial/territorial tax rate under a Canadian patent box regime?

I see no reason to reinvent the wheel compared to other countries that have implemented a patent box regime, and it is too early in the process do begin optimizing tax rates, which can be relatively easily changed in the future should the program prove to be successful. A simple median of preferential rates as implemented in other jurisdictions is a reasonable starting point.

The actual number only matters if other policy levers are used to incentivize commercialization and retention of IP that can benefit in the first place.

The Action 5 Final Report identifies the IP assets that are in-scope of a nexus compliant approach. Should all these assets be eligible for a potential patent box regime in Canada? Are there differences in business practices with respect to different types of IP assets that should lead the Department of Finance to expect that commercialization and IP location decisions for each asset would respond differently to a patent box regime?

The definitions should be expanded to include proprietary data since establishment of that definition predates the rapid accelerate of AI and ML technologies seen in the past few years. High-quality, curated data for AI and ML development is today at least as important as patents and the algorithms built using that data, and development and management of these datasets is costly and time-intensive. Income derived from licensing or otherwise making available training datasets, beyond just the models trained on them, should be included as an eligible expense in the patent box regime.

If Canada were to implement a patent box regime, compliance with the nexus approach would require businesses to report detailed information around expenditures incurred in the development of eligible IP, similar to requirements in place under regimes in other jurisdictions that are compliant with the nexus approach. Drawing on experience with nexus-compliant regimes in other jurisdictions, please share any comments on challenges and best practices in this regard.

Data collections is a critical element for evidence-based policy development that is currently missing. As previously noted in my SR&ED recommendations, any company benefitting from taxpayer-funded subsidies should be contractually required to report on use of IP for a period of no less than 10 years, and that requirement should be contractually inherited by any acquirer, assignee, or licensee of that IP. Failure to pass on this requirements should trigger repayment of the benefit.

The value provided to these companies through subsidies such as SR&ED and the patent box regime contemplated more than justify collection of the required data. A significant portion of the data on the actual development process is already collected in the process of administering SR&ED, what is missing is the long-term tracking of downstream use and flow of the resulting IP in order to assess the impact and value of these policy levers.

Design of the data collection framework, including which metrics to track, should be the subject of a separate consultation call on the subject involving all relevant stakeholders.

Are there design features of a patent box regime that the Department of Finance should consider specifically to limit new fiscal costs to the government?

Given how little income net Canadian firms receive from patents currently, I do not anticipate that giving preferential tax treatment to these assets will significantly impact tax revenues. Additionally, if my recommendations on SR&ED reform are implemented, the relevant data collection could easily be a rider to the SR&ED program, without adding any additional overhead. With savings of $1B already identified in the SR&ED overhaul, there is no apolitical reason that this could not occur as part of that effort while maintaining overall cost-neutrality.