Public Policy as Innovation Catalyst

Deloitte's recent report supports the idea that effective leadership from policymakers is a prerequisite to innovation in all contexts

In the wake of the Bank of Canada indicating that it was time to “break the glass” over the current economic stagnation in Canada, it’s worth taking a close look at some of the thought processes that are currently in the way of properly addressing it.

A while ago I wrote a response to a Globe opinion article that postulated that Canada’s poor performance on innovation was because Canadians are just not that innovative. I found the perspective mind-boggling: not only is it demonstrably wrong, given the quality and quantity of Canadian research outputs and patents granted per capita, it takes a defeatist attitude that basically accepts the status quo as something inherently Canadian rather than identifying the actual causes of the chasm between Canadian innovation output and economic activity.

Since then, I’ve seen the sentiment echoed from other voices in the innovation ecosystem, with the most worrisome being Chrystia Freeland’s comment that Canadian businesses need to do their share to bolster Canadian innovation and address our productivity challenges, as though begging for this to happen is going to move the needle in the face of policy that actively disincentivizes doing so.

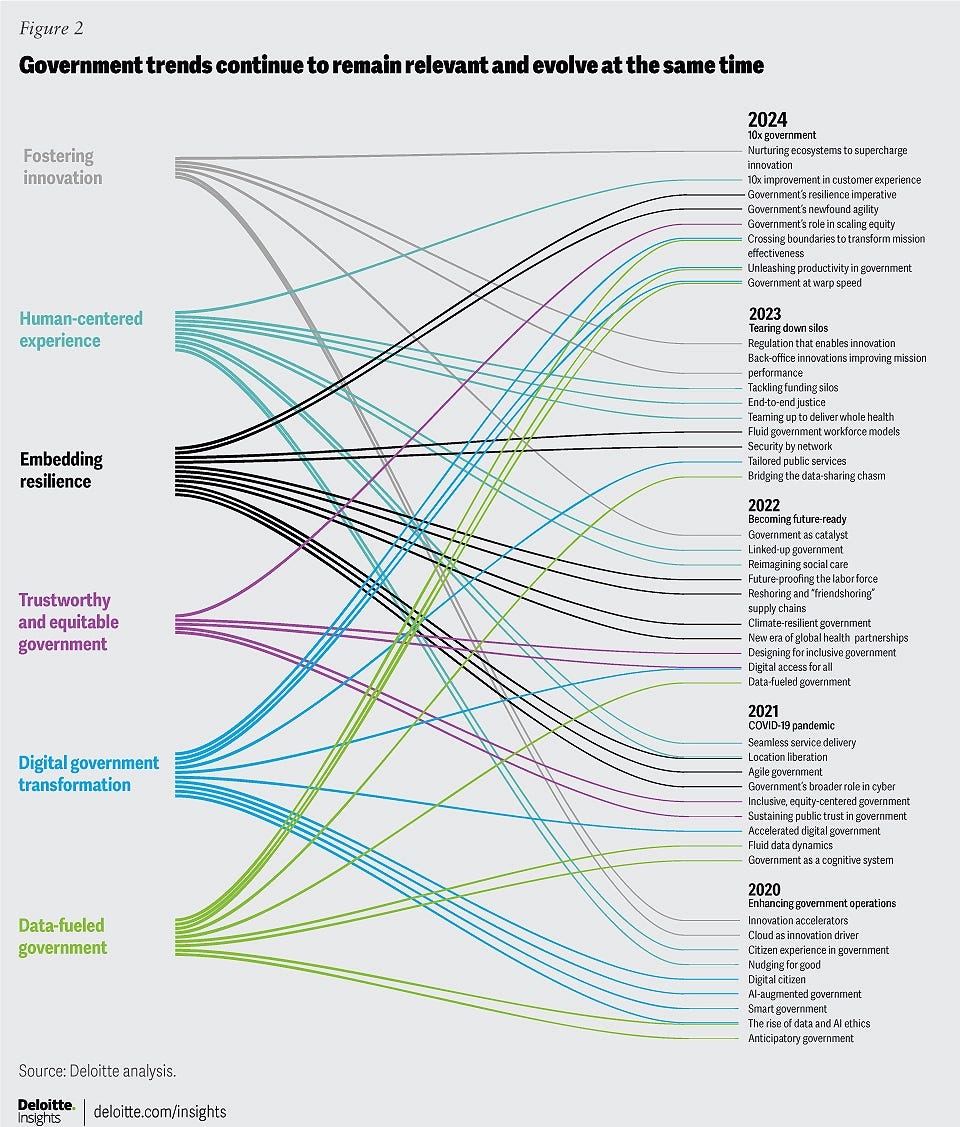

Debunking the idea that Canada fails innovation at a cultural level requires hard evidence that the problem lies elsewhere. Deloitte recently released a report entitled “The eight trends propelling the 10x government of the future” that both strongly supports the assertion that innovation requires a catalyst and outlines clearly the specific policy initiatives that make it happen. The report takes an evidence-based approach that covers 200 recent, real-world examples of radical changes catalyzed by public policy initiatives—in other words, examples of governments that embraced innovation and in so doing catalyzed the positive feedback loop. The figure below, taken from the introduction of the report, summarizes the key policy levers that have driven these changes. If you’ve been following along with CanInnovate to this point, you’ll notice many recurring themes from this blog.

Canada is caught in a negative feedback loop: economic stagnation disincentivizes domestic investment and founding of companies in Canada, which in turn reduces the both chances that Canadian businesses will succeed and the number of new Canadian businesses attempting to do so, which brings us back to square one. I have previously asserted that innovation is a feedback loop as well: when companies are supported in their vulnerable early stages they are more likely to succeed in the long run, creating an ecosystem that creates successful companies, prompting investment and interest from founders who see the ecosystem as being supportive, which feeds back into economic success. Whether stagnation or innovation prevails, it is a self-fulfilling prophecy either way.

The challenge is catalyzing the leap from the current negative feedback loop to the positive one, and it does not involve begging Canadian businesses to invest more, nor does it involve accusing Canadians of being too risk-averse. Instead, it involves sound public policy development that aims to bridge the gap and move from one cycle to the other.

There is a huge amount of valuable information in this report to unpack. Below, I summarize a few key findings of the report, along with an explicit callout for the lessons that Canada should learn from governments all over the world that have successful innovated to achieve 10x improvements, often in significantly more resource-constrained contexts than we have in Canada.

Speed and Agility in Government Service Delivery

Two of the headings in the report, “Government at Warp Speed” and “Governments Newfound Agility” focus on how recent technological advancements are being harnessed by governments in innovative ways to reduce processing times and accelerate administrative processes by orders of magnitude, challenging the idea that governments must move slowly by nature. Governments worldwide are recognizing this and embracing recent technological advancements to speed up the pace.

Gains in speed range from public-facing processes like registering a business and finding and applying for grants and scholarships, to internal processes such as processing those applications. Gains are realizing through a convergence of recently available technologies, moving service delivery to a full digital model, and using the wealth of data made available in the process to track, identify, and eliminate bottlenecks in service delivery.

One initiative in particular stands out as being particularly important for Canada: the EU’s “Just Once” initiative, which seeks to ensure that information need only be provided to the government once, and that that information be available to all other government agencies regardless of the point of entry, eliminating huge swathes of processing time.

As an example of the kind of time saving possible: many joint grants offered by a partnership between NSERC and another agency require that an application be submitted to both agencies. The aggregate content of both applications is the same, but the questions are reordered and reworded slightly, making it impossible to copy-paste information between them. Every grant to which I have ever applied, as an academic or as a business, requires fundamentally the same information, information I have now spent so much time rephrasing for each application context I can do it without thinking. Ask any Canadian academic how much time they have spent updating their Canadian Common CV, and prepare yourself for a rant. The process of effectively rephrasing equivalent content from one application to the other represents, over my career, hundreds if not thousands of hours of pointless effort that would otherwise have been spent researching, building, and innovating.

The report highlights how similar inefficiencies are being eliminated the world over. The critical enabling factor is data sharing and taking an agile approach to policy development. The former eliminates siloed data and ensures that government agencies are able to effectively and automatically access information from other agencies as required, which in turn provides the data required to inform agile, evidence-based decision-making and to iterate on policy at a pace that is consistent with the pace of technological advancement.

With proper data sharing infrastructure in place, not only are processes streamlined for businesses interacting with the government, but service delivery can be proactive, automatically identifying opportunities without the need for human intervention. A student need only enter their information once to be matched to scholarships across the entire ecosystem. Business need only maintain an up to date profile of their operations in one place to be matched to grants and procurement opportunities for which they are eligible without further intervention. Governments can assess the efficacy of policy decisions in near real time and iterate using agile processes as bottlenecks and inefficiencies are identified.

Probably the area most in need of this approach is procurement. With the Canadian Council of Innovators releasing their report on procurement this week (to be covered in a future post), there is an opportunity to carefully look at how embracing a les siloed approach to data in government can streamline the procurement process - an approach that has worked in the US already, according to Deloitte.

The infrastructure and process updates required to enable this are not something that happen overnight, and requires inter-departmental cooperation from across the entire government. More than a decade ago the Jenkins report called for “whole-of-government leadership” to drive effective innovation, a call which was evidently ignored. Given Canada’s poor and worsening economic performance relative to our OECD peers, it’s clear that this was a mistake. The best time to fix it was 10 years ago when the problem was highlighted. The second best time is right now. The longer we wait, the more costly it will be in the long run.

Unleashing Productivity in Government

When the AI revolution began with the release of Large Language Models (LLMs), Canada was in a position to lead. The Montreal Declaration was heralded as a guiding light for AI development that should have been the basis of Canada-led policy development around AI governance. Instead, the Canadian government has floundered on AI, producing little in the way of effective policy around it. Some departments have come as far as using their own chatbots internally, lagging the world by years in adoption of a technology whose innovation cycle is measured in weeks or months.

The focus of the Deloitte report around AI is on areas where governments have used AI, in particular LLMs, to streamline government processes. There is nuance here to how and where it is appropriate to use AI. An LLM is best used when the information it outputs would take a long time for a human to produce, but which takes a human only a short time to verify. Examples of this include software code (slow to produce, but quick to run and verify that it behaves as intended), automated form fill, but not submission, from an large amount of unstructured information (takes a human a long time to find the required data, but much less time to verify it given a breadcrumb), and highlighting possible challenges in policy documents for further consideration by humans (as opposed to writing or directly correcting those documents in the first place).

Though it is not explicitly called out in the report, a careful read of the examples they give provide a common theme: the key to responsible and effective LLM use in a business context is to ensure a proper chain of responsibility. It cannot ever be the case that AI takes unilateral action without human oversight. For example:

An AI system, given access to the information provided once by a business and a database of funding initiatives, can very efficiently suggest which ones are worth applying for and can even prepopulate the application forms for human review, but should never actually submit the application without approval from a human who takes responsibility for having done so.

An AI system, given the specification for a complex economic modelling problem, can produce code snippets that greatly accelerate the process of building the model, but it should only be run after careful verification by a human to ensure correctness.

An AI system can answer questions relating to complex regulations, like the tax code, pointing people to the right references in seconds for human verification, eliminating the search (N.B. not the interpretation) part of the policy research process.

An AI system can take on first-pass vetting of procurement documentation and provide real-time feedback to applicants, instantly identifying areas for improvement that might otherwise cause weeks of holdup in the process and ensuring that applications that actually reach a human are free from administrative errors and can be vetted by a human purely on the merits of the proposal only when the proposal is fully compliant with required guidelines.

The sections in the Deloitte report entitled “Unleashing Productivity in Government” is full of excellent examples of responsible implementation of such process-accelerating applications of LLMs.

They key again is data sharing. Eliminating siloes on relevant data presents a wealth of opportunities. An example in the report relates to Austria, which has automated delivery of child benefits to couples that have recently had a child. Entry of a birth record in a hospital triggers a cascade of data sharing that results in full elimination of all paperwork previously required to access childcare benefits for new parents. Combining a reduction in siloed data with a human-responsibility-centered implementation of the new capabilities of LLMs represents opportunities for millions of hours saved across administrative processes at every level of government.

In governments across the globe outside of Canada, this is already happening.

Aligning Interests in Innovation Ecosystems

As the Deloitte report points out, “Driving innovation to address complex problems isn’t simple. It typically requires influencing an interconnected ecosystem if disparate parties.”

I recently participated in a DARPA study evaluating a new piece of technology. The details aren’t overly important; what is important is that I was struck by what all the DARPA technologists all had in common: they were all people who operated in the liminal space between completely different networks, in some cases representing likely the unique human with expertise spanning their diverse areas of expertise. (As an aside, if you ever want to really experience imposter syndrome in its full glory, join a DARPA technology assessment).

Driving innovation requires the ability to think outside the box, and it is those with the greatest breadth of experience that are able to do this effectively. Since these people are few and far between, it is critical to create ecosystems that bridge networks. This becomes increasingly important as it gets harder and harder to predict what specific disruptions are actually needed. Where innovation for for the sake of economic success is the end goal, it makes sense to create the conditions in which it can happen organically rather than constraining the process to specific outcomes. Silicon valley is the prime example of this approach.

The role of government in this process is to provide incentives for private sector participation and to create conditions that incentivize participation by a diverse set of actors. This can be direct incentives, like tax breaks, grants, subsidies, and investment; they can be indirect, such as the initiatives noted above aimed at removing red tape and administrative overhead; and they can be aspirational, such as setting long-term, ambitious goals without constraining how it gets done (see for example the production of COVID vaccines, or the innovation happening in the climate space in response to long-term climate change goals).

The key point that is currently missing in Canada boils down to a very low risk appetite in the government. Even the agencies that purport to address high-risk, early stage economic development in reality rarely get involved before new ideas can stand on their own, and the administrative overhead involved in accessing support through these programs is a nightmare of inefficiency. Until policy makers acknowledge that it is OK to spend taxpayer money on initiatives that ultimately fail enroute to building the few that succeed, Canada will continue to lag. DARPA expects something like an 85% failure rate, secure in the knowledge that a single success will have such an outsized impact in the long term that the failures simply do not matter.

If you read only one page in the Deloitte report, it should be page 61. On it, the report outlines key steps that governments need to be taking now in order to foster innovation. They align well with everything I’ve been writing on CanInnovate to date, and are backed by a wealth of real-world evidence across the entire spectrum of economic development.

Innovation catalyzes Innovation

It’s worth noting that every example in the report qualifies as innovative. In this blog I often fall into the common trap of conflating invention with innovation, but this report is an excellent reminder that even something as simple as embracing new technological capabilities to streamline service delivery is itself an act of innovation that in turns enables and empowers entities outside of the public sector to do more, fueling the virtuous cycle of innovation.

If there is a single takeaway from the report, it is this: the public sector must lead the way when significant behavioral and cultural shifts are the end goal. Change starts at the top. Moving from the current negative feedback loop of economic stagnation to a positive feedback loop characterized by innovation requires leadership by example, a claim that is backed by hundreds of real-world examples presented in the Deloitte report. By following the rest of the world in embracing new ways of doing things, the government would show rather than tell its businesses that it is serious about enacting the change necessary to address Canada’s productivity slump. The rest of the world is far ahead of us. Why are we not racing to catch up?